Sideways Looks #36: A Better Internet Part 2, also Mermaids

I attempt to categorise & compare ideas for a more pro-democracy internet.

I attempt to categorise & compare ideas for a more pro-democracy internet.

Hello you,

This is a follow-up to my previous post on a more “pro-democracy” internet. It is motivated by this question: of the various ideas floating around about making online political discourse “better”, what are the theories of change, the visions and how we get from here to there? This is my attempt to collect various ideas around that into one place, and do a cross-cutting categorisation, analysis, and critique of them.

I’ve been going round and round on this piece for a while. It’s much longer than the usual one of these posts – sorry. And I’m honestly not sure I’m happy with it in the end – there’s a lot of loose threads and unexplored assumptions. But I’m a firm believer in getting ideas out into the world (see this interesting experiment); it is helpful for me to collect these various thoughts in one place; and my good friend Francesca Arcostanzo helpfully pushed me into just getting the thing done. So here it is. In future I can maybe dig down further into particular bits of it.

The next post will be shorter, more focused, and take a break from this topic for something different. Proposals/questions welcome.

Attempting to categorise "pro-democracy" internet ideas

In the last post I mentioned various approaches to developing a more “pro-democracy” internet. By “pro-democracy” internet I mean – based on what I think many of the approaches I’m analysing broadly mean – something like this: An internet which is optimised towards flows of information and participation amongst citizens, which help provide them with knowledge and power - which in turn help them participate in democracy (through voting, being or engaging representatives, sharing their views, etc.) in ways which support collective goals.

A less democratic internet might be one which is optimised – for political or business reasons, deliberately or as a side-effect – in ways which make collective decisionmaking harder (e.g. through making acceptable compromise or consensus harder, or through restricting legitimate views or productive framings), or help worsen imbalances of power. I want to reflect on some broad ideas which exist under this banner, particularly in relation to two themes.

The first is the “theory of change” underlying these ideas – what is the way they could feasibly get from situation A now to a different situation B in the future, and what assumptions and challenges are inherent in these theories?

The second theme was “how engaged do people need to be with these different approaches for them to work?”. Like, does an online voting platform need lots of citizens to participate for it to be legitimate? Would consensus-finding algorithms be impactful if only a few people use them?

But then I found just comparing ideas in terms of “participation” missed some important nuances, in particular (i) how much is the participation “run” or “controlled” by some authority, vs. being grassroots and organic and (ii) what are the expected borders of the exercise; a local area, a country, the whole world? So I added these as extra comparisons too.

What this means I am presenting four broad “models” of pro-democracy approaches to the internet and comparing them on the below dimensions.

The 4 models are: Digital Citizens Juries; Passive Political Consumption; New Coffee Houses; Better Broadcasters / Digital Public Value.

The dimensions of comparison are: Expected participation (Active <-> Passive); Authority Control (High <-> Low); Scale (Local <-> National/Global); Theory of Change.

I’m not sure whether these are definitely the right labels – for instance I can’t decide if “Authority Control” is better as “Chaos vs. Structure” – but I think they at least sort things out roughly usefully for me. I’m also not saying that these are the only dimensions for comparison, nor that all “pro-democracy” approaches would fall into one of the models – but I think lots of the prominent examples do.

Maybe by playing around with the different dimensions you could come up with new models, and perhaps save democracy. If you do, let me know.

Model 1: Digital Citizens Juries

Citizens Juries, and similar models, are designed to let public groups discuss – and maybe even change – political decisions, often regarding quite specific issues. There is a lively field of public policy studying these instruments. The example often cited is the citizens’ juries which preceded the Irish referendum on abortion, helping productively shape a highly polarising debate (compare to the Brexit referendum, which had no such preparation and managed to turn a technocratic issue into a major new angry fault-line).

The idea that digital contributions of citizens can, in principle, directly change political/governmental decisions is the unique feature of this model. This could go directly via a government or other official body (local, national, the EU, etc.). Some of the cases I discussed last time, like vTaiwan or Liquid Democracy, focus on this model. Or it could shape the priorities of a political party (see the Five Star Movement in Italy) for if and when they can wield power. Probably some other routes too but those are the most obvious ones.

So let’s apply my comparison framework:

Expected participation: Active

Active participation is important in this model. For citizens’ juries, digital or otherwise, to work you need to ensure that participants actually represent the full range of relevant views, and engage actively enough to weigh up trade-offs and practical constraints - rather than just supporting whatever sounds best. Demanding extensive participation, for its advantages, might also skew the population who can takes part (and also, extensive participation needs to be compensated).

The digital element raises with some extra aspects regarding participation. There is one clear and important advantage – lowering some barriers to entry, allowing easier participation of a wider range of people. But it also brings the risk of ‘shallow’ participation, which may not lead to a properly considered outcome. We can also think of “the NIMBY problem” – that a particular group can swing the debate by being particularly engaged, well-resourced, and/or just very present and loud. Digital settings may also allow tactics such as coordinating supporters to digitally “swarm” a vote, etc. Cleverly designed technology can help to find consensus, minimise risks of polarisation, etc; I discussed such approaches in the previous post, mostly under the "Design" heading. But these are still risks to consider, especially for highly complex and/or consequential decisions.

In some ways, and depending on the task at hand, a good Digital Citizens Jury might look quite its offline counterpart – with safeguards to make sure that people who participate are deeply engaged throughout, even if from their own homes and behind a screen and maybe with a few other tabs open in the background.

Authority Control: High

This is also important, and fairly self-evident. To ensure these events (i) produce outcomes useable by government, official bodies, or whatever and (ii) are structured in such a way to meet that aim, it is very helpful to have authorities deeply involved in the processes – though there are many questions of how much the agenda and constraints should be set by authorities, having zero control or involvement from them would probably diminish the likelihood of influencing them. One could imagine some kind of grassroots citizens’ jury coming to decisions which authorities independently choose to adopt – but there would be many challenges.

Scale (Local <-> National/International): Don’t go too large.

I am not an expert in all the literature around public participation instruments; but as I understand it, it’s important to make the topic specific, not broad or diffuse. Having clear geographical boundaries can be one way to make discussions more focused. The examples I’ve already flagged here (Liquid Democracy, vTaiwan, Five Star Movement) are focused at the level of country, or even region. For example, MeinBerlin (one of the main use cases of Liquid Democracy’s Adhocracy technology), is a platform for citizens of Berlin to learn about and express opinions on local developments. By contrast the EU-wide “Conference on the Future of Europe” had problems of unclear focus.

Country-level is already quite a big geographical boundary, to be fair. But going bigger raises more questions of how to ensure representative participation, range of potential interests, etc. So if you’re going whole-country-level, it may be extra important to make sure the topics of discussion are very specific. For example, Scotland’s attempts to do a national “Climate Assembly” seems to have resulted in largely unclear and diffuse outcomes, with mixed feelings of satisfaction amongst participants..

Theory of Change:

Some might argue that even just one instance of successful public participation in a specific and local case is a good change. I can get behind that. But if we believe there is a real crisis of democracy right now, is that enough? If you think not, like me, there’s two (non-exclusive) theories of change.

The first might be seen as a jigsaw puzzle approach – creating enough of these specific contributions that they add up to a much broader picture of change. But that requires changing underlying political systems to massively increase the number of decisions which are directly shaped by citizens, a more Swiss-style “direct democracy” model. And a reminder that Swiss-style democracy has led to a law banning burqas; it’s not necessarily a progressive or inclusive dream.

A second theory of change is that the existence of such participation mechanisms engenders a wider trust amongst citizens that their voices can get listened to, even if they themselves did not participate. So you wouldn’t need to do loads of such activities, but you’d need to make sure the ones that happened were visibly impactful, people were aware of them, and they were done in a way which doesn’t heighten polarisation around an issue (cough Brexit cough).

To conclude, both theories of change probably involve a combination of these three things, just in different amounts: Do more digital democratic participation style things, make sure they are well set up, and make sure any positive results are well-publicised. The question of how to ensure enough and diverse enough participants are properly and actively engaged is central.

Model 2: Passive Political Consumption

I think this is the model that a lot of people have in mind when they think of “politics online” – that there’s a sea of political content, some of it informative but much of it misleading and divisive, which enters people’s brains as they passively scroll social media.

Whether engaged or not, citizens have always swum in a background of political information and narratives. Sometimes these are very subtle – the political strategist Dominic Cummings used to make sure Boris Johnson was always interviewed in hospitals, on the basis that many people would see the clips on TVs in public places with no sound on, so what he said was less important than the background optics.

On social media this feature may be heightened by so-called “context collapse”, in which personal/family discussions, entertainment, advertising, politics, and more all mix together in one feed. As such, particularly at times of heightened political tension, it can become hard to avoid political narratives even for “disengaged” people. (I have written about whether this is actually a good thing previously). But in general, these narratives are just hanging around in the background as people scroll, interspersed amongst other content.

So, comparison time.

Expected participation (Active <-> Passive): Passive

“Passive” is in the name – this model is all about what happens when participants are passively absorbing political messages. It’s working on the central assumption that a lot of internet use is so-called “lean back” activity, i.e. passive consumption, and that this is hard to change. I’m going to deal with more active, engaged participation in the next model.

But to be clear – “passive” does not necessarily mean stupid, gullible, uncaring or completely disinterested. There’s been a lot of exaggeration about how people may be misled by online “fake news”, which tends to presume a certain level of dumbness. Passiveness may just be busyness, a feeling of overwhelm, temporary disengagement, etc. etc.

People can also be very active about some things and passive about others. I’m talking here about people who are passive in regards to content about politics. They may see a few politics posts in their feed, which may make them learn / be happy / be annoyed about some particular issue or person or event, but then they’ll move on to something else.

Authority Control (High <-> Low)

Low. This is the classic Bill Clinton “it’s like nailing jelly to the wall” argument about the internet – the only way to control what people see as they scroll online is to be highly authoritarian, suppress free speech and access to information – Great Firewall of China style. Any attempts to allow (mostly) free speech online but with some regulations, whether EU or US style, are extremely challenging (not to say we shouldn’t try, but it’s challenging).

This lack of control or clear “authorities” is exactly what makes some people so nervous about the internet. Who to believe? What stops people saying whatever they like? Sometimes this is unfair; traditional authority voices can also be mistaken or misleading, suffer from groupthink, focus on certain issues, etc., and the internet gives a chance to widen discussions past that. If you’re careful and open-minded, the internet is a great tool to check and expand on stuff you read. But then we’re probably expecting people to be more active, and this model assumes that is an unrealistic solution en masse.

But important addition: Even if there’s less control from traditional authorities, there are important authorities in the background – the platforms. They can set rules, like what is allowed and disallowed etc. But perhaps more importantly, it is their algorithms that determine what content gets visibility. This is often similar to long-standing media logics – sensational, often controversial, material is likely to get engagement. But it’s also hypercharged compared to old-style media. First, there’s usually fewer limits on how sensational you can go. Secondly, when content gets engagement the algorithms read that as “good content” and push it to more people. So there are incentives to sensationalising, playing the algorithm game, etc. – and in politics, that can veer into being controversial, polarising, misleading etc.

Scale (Local <-> National/Global)

Again, like nailing jelly to a wall – it can be often difficult to stop conversationalists and conversations mixing from many different geographies, areas, etc. This has its advantages; we can learn more from and about different countries. But it also has the risks that populations of certain countries, like the USA or India, dominate discussions simply by (i) numbers of people and/or (ii) their geopolitical importance. And, of course, the risk of governments or other powerful actors using digital spaces to try and influence or destabilise political discussions in other countries. Again, this can be overblown or oversimplified; but should certainly not be ignored.

Theory of Change

There’s a few theories of how passive internet use becomes political change.

The first is that some narratives become so visible online and are “absorbed” by citizen at a large enough scale to make an impact. The concern is usually that this might be some fake or misleading news, particularly prior to an election, but as I have written before I find this gets too much attention. I’m more interested in “affective” and emotional questions around whether narratives mean people don’t just disagree, but actively dislike people with other opinions, or absorb a sense of pessimism and crisis about the state of the world. This should not be blamed entirely on the internet – such an argument risks dismissing real concerns, from economic to geopolitical to domestic. But in such a tense and negative environment as today, it is probably not helpful if social media is optimised for such forms of communication.

A lot of the proposals to address this focus on giving users more choice. That may be “algorithmic pluralism” or “middleware” to better choose what sort of content we get recommended as we scroll, or “the Fediverse” and “interoperable platforms” so we can easily move between different platforms if we don’t approve of how one platform is being run. Some of these approaches might use the sorts of consensus-building and polarisation-reducing algorithms mentioned in Model 1.

I’m generally pro things which give people more choice, and potentially create more competition for big tech platforms and their owners. I’m just not sure that’s enough to make people adopt the technologies en masse. This idea presumes people are engaged enough to want to engage with these different choices. And the whole presumption here is that people operating under this model are passive. En masse use of the newer technologies might happen if new technologies provide a much better experience overall, or in other fields (e.g. entertainment), and provide a better passive experience of politics online as a side-effect. But I think a lot of these emerging approaches may be designed with politically engaged (or maybe highly engaged in other ways, perhaps with new tech or deep information-seeking) people in mind.

As such I’m not clear they can address the issue at hand in this model: that the politics which reaches largely disengaged people as they scroll social media might be optimised for sensationalising, polarising, divisive content. Solving this problem is, to be fair, a big ask (and it is very hard to pin down exactly how large a problem that is). Proponents of such new technologies might not even be attempting this mission – they might be squarely aiming at engaged people, or specific contexts, as addressed in other models in this piece. But if so, I think that needs to be clear. And I’m not sure that clarity is always there.

A second option, which doesn’t rely on users actively opting for some new technology which helps them avoid polarising clickbait, is to somehow force the platforms to adopt as a default “better” approaches to hosting online content about politics. I think the EU’s Digital Services Act is trying to push a little in this direction, by making platforms do risk assessments against the worst parts of online political discussion (vulnerability to malicious strategies, hyperpolarising or radicalising content, etc.). But if you start saying that platforms have to go beyond “avoid the worst stuff” and into “do good”, you have to agree on what “good” is – and finding one “good” way to do political discussion is, well, unlikely.

(An important example is Meta's (now changed) approach of making political content less visible, on the argument that this is a method for taking the heat out of online discussion. But it also probably restricted access to the sorts of information that is important in democracies. This was a dangerous “quick fix”, but a fairly logical conclusion of arguments that 'politics online is divisive – so let’s just get rid of it'.)

So overall the idea of forcing platforms to be less-worse at hosting online discussion may be feasible, but forcing them to be good at it has loads of conceptual and practical problems.

A third theory of change is that the digital environment can convert disengaged individuals into engaged individuals. To again use the example of Cummings, the Brexit campaign he ran used targeted adverts for a Euros betting contest to football fans “which gathered data from people who usually ignore politics”. There is a plausible hypothesis that this sort of conversion may be happening with the various successes of radical parties with young people through things like TikTok and Manosphere podcasts.

This need not be conversion to a particular political party of ideology; there’s some evidence that Covid conspiracism could have been a “gateway drug” to more general conspiracism and anti-establishment-ism. Maybe, however, there’s more positive versions of that. Maybe this is the route to the solutions proposed in the previous paragraph. But we should leave that to the next model, which specifically focuses on active participation.

A fourth (and final) theory of change is that political leaders could get better at playing the existing algorithmic systems in ways which get attention and engagement from the scrollers without resorting to sensationalism. One of Ezra Klein’s recent podcasts suggests that politicians like Zoran Mamdani Mamdani simply “get” this style of communication better – see this popular and very funny recent example - so can use the format to distribute a range of messages (though I’m sure Mamdani’s opponents would argue he did a lot of polarising and simplifying content too). I also find Klein’s argument a bit depressing in that it seemed to sublimate skills of developing policy to skills of gaining attention. That’s always been the case in politics, I guess, but the competition for attention has become ever more personalised and ever more competitive.

So overall, I’m afraid, I leave this model somewhat pessimistic. But what about when people are more engaged with politics online?

Model 3: New Coffee Houses

Many figures have referred to social media as a “new coffee house”, or a “new town square” or similar. The most prominent such voice on the internet as “public square” is Elon Musk, though he seems to think public squares are best served by flooding them with pornography, handing megaphones to any fraudsters who pay for blue ticks, and applying inconsistent rules to support “freedom of speech” of anyone who agrees with him and censor those who don’t.

Anyway, *breathes*.

These models perhaps have rosy-eyed views of town squares and coffee houses, but the in-principle ideas are something like this. They are spaces where people came to actively exchange views with and learn from each other, even total strangers, about issues of the day. Some of these people may have particular expertise or experiences, or non-mainstream views or ideas, and you hear these views without mediation via e.g. newspapers. Such discussions can help spread ideas which shape people’s beliefs, what they care about, encourage them to challenge dominant political narratives, etc.

Expected participation (Active <-> Passive): Active

This model is similar to the previous one with a key difference: here we’re focusing on people who are actively engaging with political discussions online. Importantly, being engaged can take different forms. You can writing your own posts and comments. You might also be silent, but very actively, searching around seeking detailed information and views on particular topics. You may be permanently engaged across a lot of topics, or you may be focused on one thing, perhaps even only temporarily. Perhaps our passive scroller above saw something that piqued their interest, and they temporarily seek out more information about it, etc. etc.

The big distinction between a physical coffee house and the internet is the sheer volume of information and content – how do you filter and prioritise it? We’ve already discussed the role of algorithms above (and the potential risks involved, if the algorithms are optimised for things which may help retain attention but may not be best for political discourse).

Under this model, particularly dedicated users may get round this by putting in the effort to curate sources. This is a great way of using the internet to its full potential. Many of the smartest and most well-informed people I know are curating a range of forums, blogs, social media accounts, to get a range of perspectives and follow in-depth discussions. Alternatively/additionally, people may explore the options such as Middleware and the Fediverse I outlined above, to optimise their systems.

However, we can’t assume that even engaged people will take these steps. Many will just accept the algorithmic recommendations and get them full-force. Others may put the effort to curate sources or use technologies which all give a certain perspective, potentially leading to a rabbit-hole of radical opinions.

Authority Control (High <-> Low): Low.

Similar to the above, even trying to control the discussion is hard. But there’s also an important additional factor: too much control by “official” authorities risks the novelty and diversity of potential ideas which this model offers; and also people interested in such things may just congregate somewhere less controlled. Some control is needed to also ensure the spaces allow productive discussion, but how much control is a hard question. It will vary between different spaces, and different methods of moderation. But it can’t go as far as broadcast and agreement of one “official” point of view, and room for some uncomfortable discussions will probably be important.

As above, again a reminder that platforms themselves play important roles as “authorities”, including via algorithms and recommender systems. As discussed above, under this model some users may put the effort in to avoid or personalise this; but maybe not, and heavy users may even be more subject to the particular interests of platforms (see “power users” of X being extra-exposed to Musk-friendly views).

Scale (Local <-> National/Global)

Same as Model 2 – can be hard to pin these discussions down to geographic borders, with the benefits and risks that entails. This may include, in this particular case, people trying to import ideas which work well in one political culture (probably the USA) to other places – maybe productively, maybe inappropriately.

Theory of Change

Similar to that of Model 2 – people’s beliefs, ideas, attitudes etc., are shaped by the narratives they receive, including online. If we’re thinking about politically engaged people, it’s likely they’ll be smaller in number than those under Model 2 – but it could still involve people, e.g., gathering an array of views to genuinely decide how to vote, particularly around an election, or people who can spread useful discussions more widely, etc etc.

As hinted throughout the above, I think a lot of the ideas discussed under Model 2, of the Fediverse or Algorithmic Pluralism or so on, make more sense under this model. They require, and reward, deeper and more purposeful engagement. That won’t be universally true of all engaged people – someone who has temporarily become deeply interested in a particular topic is unlikely to completely reconfigure their social media around it. But they at least make it harder for information-gathering to be so monopolised by a few technologies shaped by people with their own, potentially non or anti-democratic, priorities.

A second theory of change is that engaged people may be smaller in number, but include influential political “vectors” who take views from their online spaces and move them into positions of power and influence. In the past it may have been political philosophers whose coffee-house-inspired ideas went on to further inspire leaders and activists. But nowadays it seems, for example, that many of the dominant “new right” thinkers influencing the Trump administration are the sorts of people who have developed their ideas and ideologies from being “very online”. Some of their outriders, most notably Joe Rogan, are also part of this “very online” pipeline from (e.g.) “men’s health and fitness” to radical right-wing politics. And some of these groups are sharing profoundly anti-democratic ideas. Authors from Jamie Bartlett to Julia Ebner have discussed how the internet is a crucial way for networking radical ideas, including some deeply regressive and anti-democratic ones, which can then gain more mainstream influence.

Of course, tools to enable deeper engagement online have also enabled various things that could count as more pro-democratic. For instance: great online investigative journalism and similar work, holding power to account (see e.g. Bellingcat or 404 Media); alternative media and organisational capabilities in autocratic regimes (see e.g. the importance of YouTube to Alexei Navalny); raising awareness of important abuses of power (progressives might point to #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter as particular examples). And also just playing a role in making everyday people more aware of and engaged in politics - converting the disengaged to engaged definitely doesn’t always mean creating radical conspiracy theorists, of course.

But engagement can be directed in many ways, not all of them pro-democratic. Creating tools to empower users and many alternative spaces for political discussion may make it harder for any one person to push the direction of engagement – in particular if Zuckerberg continues to head in Musk’s direction, optimising his platform in a more Trump-friendly way and making misleading statements about censorship from Democrats (and remember that Meta has many many more users than X). But users can also decide to head off in anti-democratic directions of their own volition.

(Ben Smith’s book Traffic is very good on how the ‘Huffington Post’ generation thought they had captured the internet for liberals, only to watch Breitbart and other far-right outlets learn the tricks and turn the tables).

In general: Like lots of the other technologies mentioned above, I think the idea of giving engaged people tools to facilitate deeper and wider information-seeking and discussion is a good. But it may not always support overall pro-democratic outcomes.

Again, quite depressing. Sorry. Let’s move onto a final model.

Model 4: Better Broadcasters / Digital Public Value

This model is kind of two-for-one, and I haven’t settled on which title captures the important bit better. The first idea, “Better Broadcasters”, is quite simple: Models 2 and 3 have focused on the demand side of content, but what about the supply side? What can we do to encourage producers of content to be more reliable, avoid undue polarisation, etc.? A few previously-discussed points touch on this – for instance if recommender systems promoted content which was more reliable and informative than sensationalist and divisive, that would incentivise producers. But what might other approaches be?

There’s a fairly extensive and growing discussion related to this question, often under this heading of “digital public value”. This is the idea that public-interest institutions – particularly public broadcasters – should play a more dominant role in shaping modern information ecosystems. As the latest Reuters Digital News Report shows, public broadcasters still have a powerful role in many countries – in the UK the BBC is by far the biggest source of news both on- and offline, in Germany ARD and ZDF dominate offline news (the online picture is more mixed, but ARD still leads, and also Germany is relatively less online than many other wealthy countries).

But there are concerns that such “establishment” institutions may be outcompeted in the modern digital age world, and replaced by more online-savvy options – quite possibly driven by particular economic / political / need for attention incentives to provide less reliable or overall “healthy” contributions to the information ecosystem. The hyperpartisanship and “alternative realities” of the USA are held up as an example of what happens when a media environment has less strong public broadcasters; but also as a broadcast style which seems to work well online.

So there’s been efforts to consider how such public institutions can provide more value attuned to the digital world. This ranges from digitising archives of public-interest material, to improving how public broadcast content can be accessed on digital platforms, to considering how to make better use of comments left on their content online, etc. Sometimes this involves them innovating their own websites and platforms, other times considering how they share their content on other platforms. Many of these efforts stretch back even before the social media explosion in the 2010s. The always interesting (and extremely nice) Bill Thompson wrote a very good piece on the history. But concerns around social media have supercharged the discussions.

Now, I don’t want to fall into the trap of saying public broadcasters are necessarily “better” than other sources, totally “neutral” or “unbiased”; they do still have staff with journalistic and often elite biases, so they will still often aim for attention-grabbing headlines. And, of course, such outlets can have strong risk of being behold to the government (though so can other media). But I do believe there are, in general, incentives for them to be more careful, balanced, and reliable than non-public outlets. I overall believe that they are a valuable part of an ecosystem, if other voices are also able to challenge them on things they miss or misrepresent.

More broadly, this model basically works on the assumption that there are broadcasters who (i) see a key part of their role as providing reliable and accurate information as a public good (ii) have structures and incentives to do so, even at the expense of things like moving fast or trying to sensationalise or polarise for engagement and (iii) have enough resources and structure to be thinking about structural questions beyond “make good stuff, post it online.” Hence use of the more general name “Better Broadcasters”.

Expected participation (Active <-> Passive): More Passive

Generally the idea in this model is broadcasters are considering how they produce and share things for audiences to consume – so largely a one-way flow of information to passive audiences. There are occasional suggestions that broadcasters would be able to make better use of “user-generated content” – it’s mentioned in ZDF’s report on Digital Public Value, and also their “Public Spaces Incubator” work with New_Public refers to technologies discussed in the other models, including new ways of ranking content and integration in the Fediverse. But, as I’ll discuss more later, I’m not entirely clear what ultimate role they see this playing.

Authority Control (High <-> Low): High

As noted above, this model assumes broadcaster(s) with incentives and processes for producing “reliable” and “quality” content. Again they may still make mistakes, be misleading, be biased towards certain stances, etc. But it’s not like e.g. Joe Rogan, who repeatedly says misleading things and then later (sometimes) says “well I may have misspoken, whoops, anyway let’s carry on” with very few consequences. These incentives may even (particularly for public broadcasters) include official regulations or other accountability mechanisms.

(If you’re wondering why I keep bringing up Rogan – see this from the Reuters Digital News Report: “One-fifth (22%) of our United States sample says they came across news or commentary from popular podcaster Joe Rogan in the week after the inauguration”. That is a serious rival to many mainstream media offerings).

So this model still has more authorities and controls involved than either Model 2 or 3. This may push back on some of the (real or perceived) “wild west” feel of the other models. But it comes with risks of being seen as “establishment”, being inflexible or slow, and not necessarily being optimised to compete in a social media age. I think a lot of the questions these broadcasters are asking themselves are about navigating this tension.

Scale (Local <-> National/Global): Largely National

Most of the key examples I’ve mentioned are on national public institutions, but there are also international collaborations, including the Global Task Force for Public Media and the Public Spaces Incubator project – though again they seem quite traditional, in a sense of sharing learnings, co-producing shows, or just generally advocating for their members. But watch this space I guess.

(Funny coincidence, I used to act with Emma Moran who is one of the writers in the afore-linked BBC-ZDF co-produced show. She is very funny and very nice – and, it turns out, doing a lot of cool stuff).

Theory of Change

As outlined in the introduction to this section, I think this is largely a theory of “stop things getting worse” – avoid entirely hyper-fragmented media environments driven by private and/or partisan interests. Given this model also works with passive consumption of media, I think this is particularly relevant in relation to the aforementioned Model 2 – ensuring that news and political content experienced in passive scrolling doesn’t entirely consist of sensational or partisan material.

In order to have this impact, however, their content probably needs to be quite a substantial part of online discourse. I like the idea of public broadcasters – or just more well-resourced “reliable and middle-ground” broadcasters – being or staying a big part of our information ecosystem. I also support ideas and innovations for such broadcasters to make better use of available digital technologies. But I still don’t fully see how these two things connect – how the innovations will realistically, in our current platform environment, lead to them out-competing other voices online.

As mentioned above, there are also hints of ideas focused on more active participation, particularly around user-generated content. A lot of it still feels unclear and speculative to me, and I’d like to know more about the ends which (e.g.) ZDF sees such user-generated content contributing to – actually shaping the material they broadcast, creating a discussion culture amongst their audiences and followers, seeping into and shaping wider online discussion culture…? But these efforts could maybe, at a smaller scale, help improve discussion technologies and cultures which may support efforts in other models (esp. Citizens’ Juries or the Coffee Houses).

Maybe I’ve missed something – as I say, there is quite a lot of emerging literature on these ideas. But from what I’ve read thus far, I’m not always clear on the theory of change (and when I attended the launch event of the ZDF report, lots of the questions implied the audience weren’t clear either). Often the idea of innovating public broadcasters is seen as a good in its own right – which I agree with, but it’s not a clear solution to a crisis in our democratic information environment. And as is a central thread of this piece, I think a theory of change should be explicitly outlined in order to consider and critique the assumptions (e.g. about expected audience engagement) and how to design implement the ideas accordingly.

Quick Edit 27.07.25: I realised I missed an important addition - similar to politicians in Model 2, the individual journalists and others at these outlets could get really good at doing communication optimised for current formats - a "BBC Joe Rogan" or "ZDF Mr. Beast". The problem here is that requires flexibility, experimentation, taking risks etc. - so better to do that as an individual (perhaps after building up a reputation within an established insitution)? But then, maybe you could still be an individual but aligned with some of the established institutions? Sophia Smith Galer is an interesting proponent and analyst of this idea.

Conclusion

I’ll conclude by just collecting and reiterating some running themes. The first is that I am genuinely positive about, and excited by, many of the individual technological developments mentioned here.

The second is that I’m still unclear how these technologies add up to a more “pro-democracy internet” on a larger scale. “Unclear” isn’t a euphemism for “I don’t think they can”. I just see many ways in which these technologies could create pockets of better-informed or more involved people – some of whom may use that to inform themselves against democracy. Citizens Juries could be an outlet for xenophobic policies (see the Burqa Ban popular vote in Switzerland); Digital Coffee Houses can, as we have seen, connect actors and ideas who are aiming to undermine democracy. That’s not a de facto argument against helping people get better information – after all, who gets to decide what is “better information”? But it’s not clear path to a more democratic discourse.

Theories of change aren’t just visions for something better; they also involve making the assumptions explicit, and discussion of whether they are severe barriers to success and/or imply difficult trade-offs somewhere down the line.

Perhaps the most convincing vision I see is actually not change, but rather stopping our information environment getting worse – information flows and participation becoming even more strongly shaped by and for partisan or business interests. Protecting from this would, in itself, be valuable. But I feel a need for more.

A third and final thought. In analysing society, it’s common to speak in terms of loops – X affects Y which affects X and so on. In this case, we’d think of how our broader politics affects our information environments, which affects our broader politics, and so. But I think it’s valuable to go beyond just a loop, and ask if one direction of impact is more powerful than the other. And as I wrote this, I felt more and more strongly that the [politics -> information environment] direction is the stronger. The dissatisfaction with political leaders, with economies, with domestic and geopolitics, with democracy itself – that directs how technology is used, what people want to say and want to find.

Which means: The outcomes of many of the ideas we’ve discussed seem path-dependent on what is already dominant in our political culture. It raises questions of how to improve our politics in ways which don’t rest so strongly on changing our information environments. That, I believe, starts with better political leaders. Something we’ve often been asking for since politics began.

So, we got to the end. That was a lot. And each time I re-read I find something to re-consider or dispute. But it was useful to get it out there, and I’m leaving it now for you to consider and dispute instead. I’ll end with a quote from Bill Thompson’s excellent piece noted above, which – as so often with Bill – holds up that important mix of cynicism and optimism:

“since those relatively innocent days the open internet has become the toxic internet, and as you may also have noticed, we haven’t made any real progress on building a usable digital public space… [but] I haven’t given up on these ideas.”

Fun Fact About: Warsaw

I visited Warsaw for the first time recently, to give a talk at the College of Europe in Natolin. There are lots of facts about Warsaw, many of them not-fun – the Warsaw Uprising and its aftermath, for example – but also a couple of fun ones. I learned a fun thing about an apartment which is very narrow at the front but very wide at the back, allegedly because property was taxed on the number of front windows, but I’ve been unable to substantiate it so shall not treat it as a fact.

So I leave you with this story about the historical connection between Warsaw and mermaids – which is why the logo for their public transport has a fish tail.

Recommendations

A repeat reminder: For those looking for or offering Tech Policy adjacent jobs in Europe (including the UK, sob), I continue to run a Googledoc of jobs I hear about (updated more sporadically than I’d like, but you can also add jobs yourself).

Lawfare, which I have recommended a lot here previously, has a new podcast Scaling Laws specifically about AI and the Law. I’ve listened to two episodes, I’m not a 100% fan – I think it focuses a bit too much on the sorts of risks that interest Silicon Valley, not enough on e.g. discriminatory impacts, and the hosts’ geeky-blokey banter is a little annoying sometimes – but it’s still a very detailed and interesting and valuable listen.

As I keep recommending serious podcasts, for German-understanders I’d recommend the extremely funny “Too Many Tabs” podcast about random rabbit-holes online. The latest one is a round-up of great animal stories. Even if you don’t understand German, the hosts cracking up while mimicking a bear running a munitions centre at 23:30 is still joyous.

I can’t remember if I’ve ever recommended the politics/strategy blog Comment is Freed by father-and-son duo Lawrence and Sam Freedman, but it’s consistently excellent. Sam’s interview with the author of When The Clock Broke, tracing the precedent of Trumpism in the 1990s, was a particularly good recent post.

A keyboard shortcut that I use loads but recently realised is maybe not well-known. On a Windows keyboard, if you press the windows key + V, you get a popup list of everything you’ve copied recently and can choose which to paste (on Apple it’s apparently Shift + Command + V). It may not sound useful, but honestly I find I use it so often.

A slightly random one here, but what the heck you’ve made it this far. A (possibly niche) form of background media / procrastination I enjoy is videos of live performances of song. At the moment I’m having an “ostentatious indie” phase so was delighted to discover a video of Florence + the Machine “No Light No Light” with an incredible theatrical over-the-topness to match the song (though admittedly the audio isn’t as good as the original). But for real aficionados of this entertainment form, FKJ’s non-stop 1h30 solo gig on the salt plains of Bolivia is impressive and extremely beautiful.

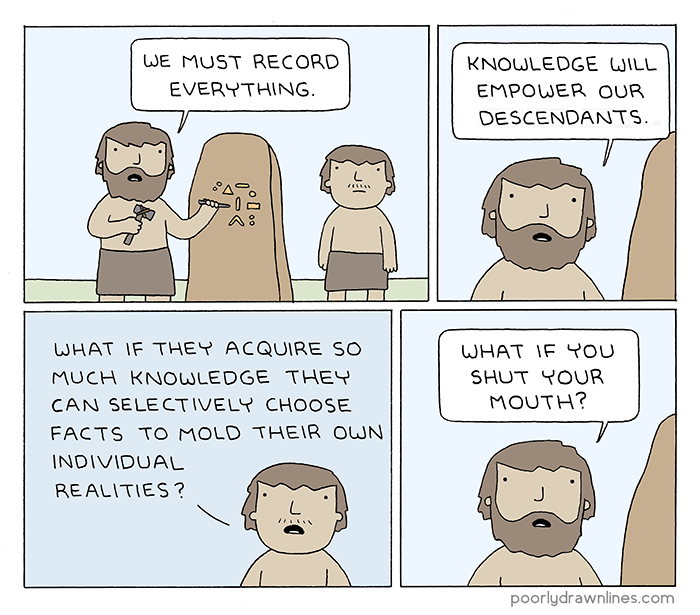

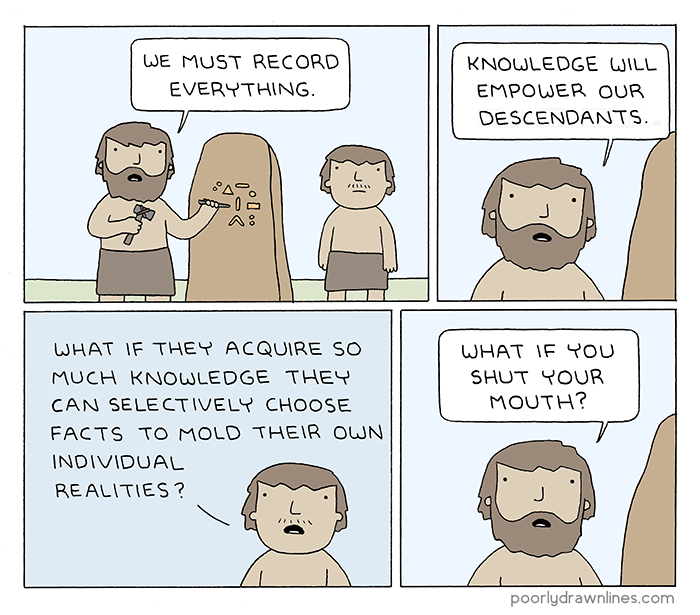

Finally - I have been decorating my apartment. I visited a friend’s apartment and (i) she turns out to also be a fan of the Poorly Drawn Lines comics and (ii) has hung a couple on her wall as decoration. I stole this idea. The one which always gets the best response is this. Though perhaps given the nature of this newsletter, this would be more appropriate https://poorlydrawnlines.com/comic/knowledge/